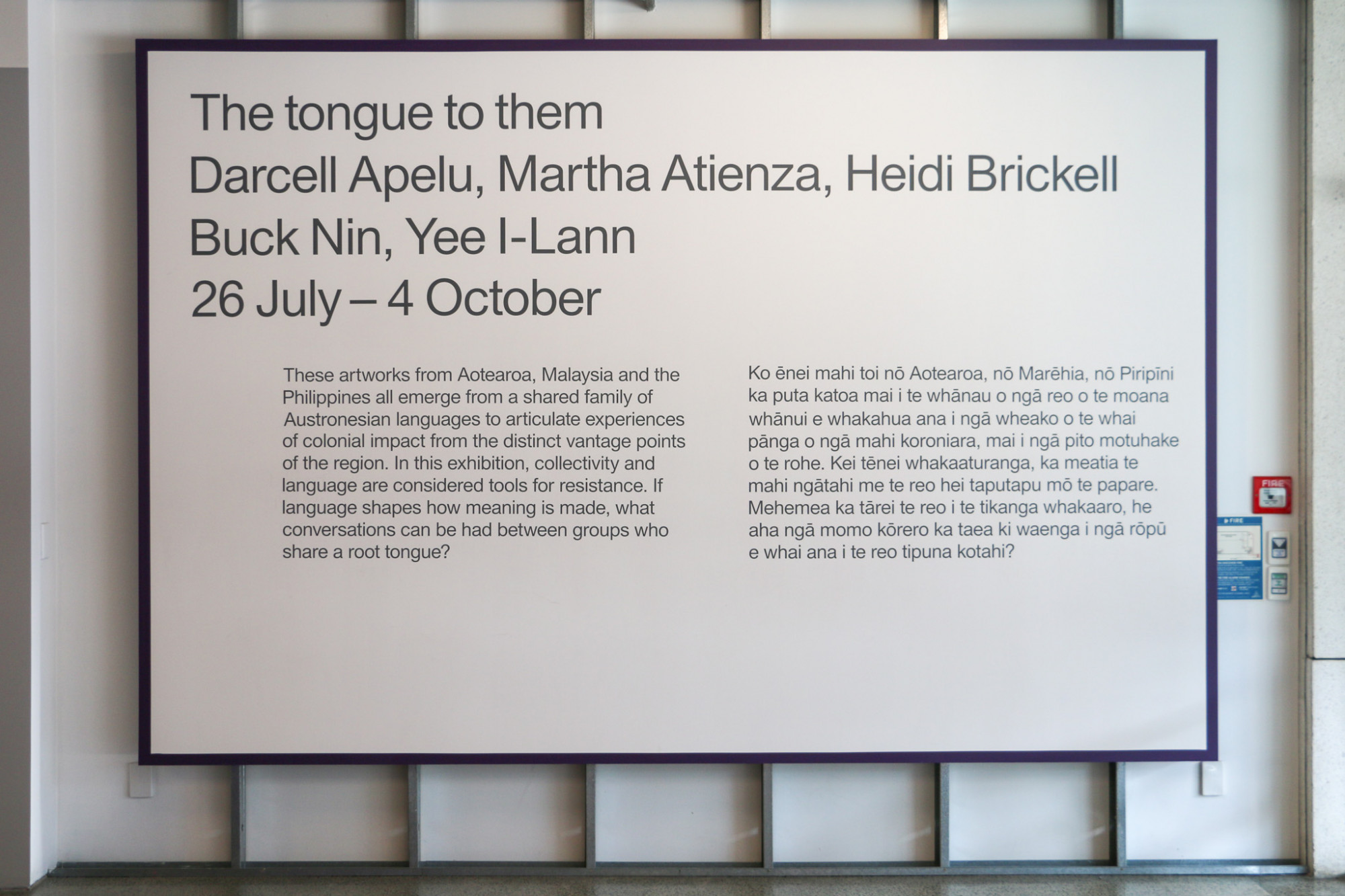

The tongue to them

Darcell Apelu, Martha Atienza, Heidi Brickell, Buck Nin, Yee I-Lann

Yee I-Lann, TIKAR/MEJA, 2018–2023. Bajau Sama DiLaut pandanus weave, commercial chemical dye, dimensions variable.

The tongue to them, 2025. Installation view.

The tongue to them, 2025. Installation view.

Darcell Apelu, Ingress/Egress, 2025, cut perspex in Cherry Satin, 230 x 262 x 110 cm; floor vinyl with matt laminate, 130 x 1330 cm; Yee I-Lann, TIKAR/MEJA, 2018–2023, Bajau Sama DiLaut pandanus weave, commercial, chemical dye, dimensions variable. Weaving by the nomadic sea-based Bajau Sama DiLaut people: Sanah Belasani, Kinnohung Gundasali, Noraidah Jabarah (Kak Budi), Kak Leleng, Kak Horma, Makcik Bilung, Roziah Binti Jalalid, Dela Binti Annerati, Erna Binti Tekki, Abang Boby, Adik Alini, Adik Aisha, Darwisa Binti Omar, Adik Marsha, Dayang Binti Tularan, Tasya Binti Tularan, Shima Binti Manan, Adik Umaira, Abang Tularan Sabtuhari.

Yee I-Lann, TIKAR/MEJA, 2018–2023, Bajau Sama DiLaut pandanus weave, commercial, chemical dye, dimensions variable. Weaving by the nomadic sea-based Bajau Sama DiLaut people: Sanah Belasani, Kinnohung Gundasali, Noraidah Jabarah (Kak Budi), Kak Leleng, Kak Horma, Makcik Bilung, Roziah Binti Jalalid, Dela Binti Annerati, Erna Binti Tekki, Abang Boby, Adik Alini, Adik Aisha, Darwisa Binti Omar, Adik Marsha, Dayang Binti Tularan, Tasya Binti Tularan, Shima Binti Manan, Adik Umaira, Abang Tularan Sabtuhari. Detail.

Yee I-Lann, TIKAR/MEJA, 2018–2023, Bajau Sama DiLaut pandanus weave, commercial, chemical dye, dimensions variable. Weaving by the nomadic sea-based Bajau Sama DiLaut people: Sanah Belasani, Kinnohung Gundasali, Noraidah Jabarah (Kak Budi), Kak Leleng, Kak Horma, Makcik Bilung, Roziah Binti Jalalid, Dela Binti Annerati, Erna Binti Tekki, Abang Boby, Adik Alini, Adik Aisha, Darwisa Binti Omar, Adik Marsha, Dayang Binti Tularan, Tasya Binti Tularan, Shima Binti Manan, Adik Umaira, Abang Tularan Sabtuhari.

Yee I-Lann, TIKAR/MEJA, 2018–2023, Bajau Sama DiLaut pandanus weave, commercial, chemical dye, dimensions variable. Weaving by the nomadic sea-based Bajau Sama DiLaut people: Sanah Belasani, Kinnohung Gundasali, Noraidah Jabarah (Kak Budi), Kak Leleng, Kak Horma, Makcik Bilung, Roziah Binti Jalalid, Dela Binti Annerati, Erna Binti Tekki, Abang Boby, Adik Alini, Adik Aisha, Darwisa Binti Omar, Adik Marsha, Dayang Binti Tularan, Tasya Binti Tularan, Shima Binti Manan, Adik Umaira, Abang Tularan Sabtuhari. Installation view.

The tongue to them, 2025. Installation view.

Heidi Brickell, Either Way Ka Mate, 2023–2025, rimurapa, rākau, cotton twine hand-dyed with acrylic, ply, shellac, adhesive, dimensions variable.

Heidi Brickell, Either Way Ka Mate, 2023–2025, rimurapa, rākau, cotton twine hand-dyed with acrylic, ply, shellac, adhesive, dimensions variable. Detail.

The tongue to them, 2025. Installation view.

Martha Atienza, Anito 2, 2017, single channel HD video, colour, audio on speakers, 7:18 minutes, looped.

Martha Atienza, Anito 1, 2011–2015, single channel HD video, colour, audio on speakers. 8:08 minutes, looped.

The tongue to them, 2025. Installation view.

Buck Nin, The First Arrivals To Aotearoa, 1996, lithograph print on paper, framed, 71 x 90.5 cm, edition 37/200.

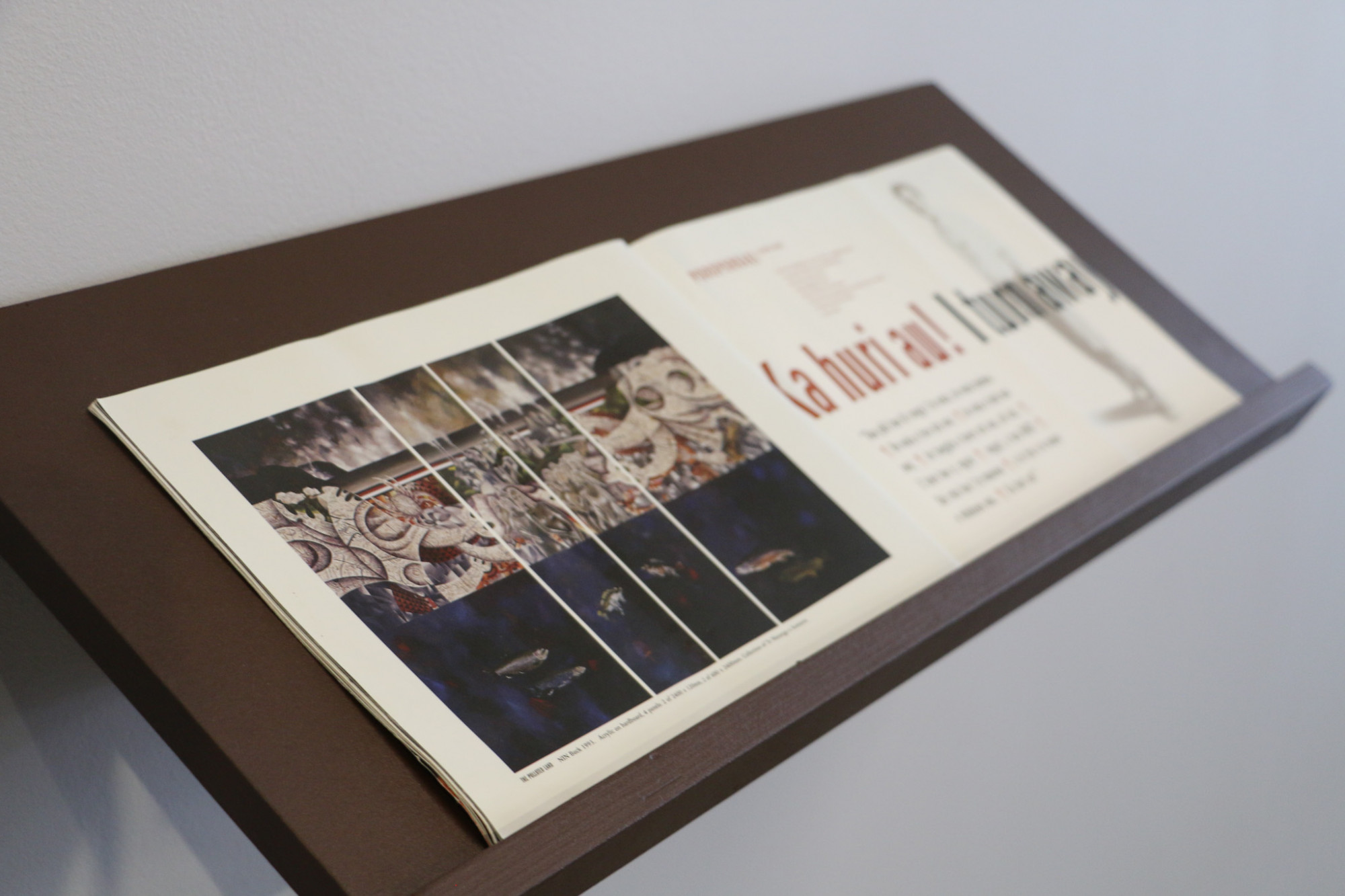

Buck Nin, The Polluted Land, 1993 [offsite], acrylic on hardboard, 4 panels: 2 of 240 x 120 cm, 2 or 60 x 240 cm.

The Polluted Land remains offsite at the Te Wānanga o Aotearoa Te Puna Manaaki head office in Te Awamutu. This is viewable during their opening hours Monday to Friday, 9.30am–4.30pm.

Buck Nin, Forever Buck Nin, 1998, publication on the occasion of a major retrospective of the same name originated by the Porirua Museum of Arts and Cultures. Installation view.

These artworks from Aotearoa, Malaysia and the Philippines all emerge from a shared family of Austronesian languages to articulate experiences of colonial impact from the distinct vantage points of the region. In this exhibition, collectivity and language are considered tools for resistance. If language shapes how meaning is made, what conversations can be had between groups who share a root tongue?

This exhibition is presented in association with Te Whare Toi o Heretaunga Hastings Art Gallery and with the support of Te Wānanga o Aotearoa.

View full exhibition text

The family of Austronesian languages encompasses a huge geographic spread that is spoken across Southeast Asia, Micronesia, Melanesia, Polynesia, and Madagascar. A family of languages is determined by a common ancestor language and enough shared particulars that give form to a dialect, such as its structures, semantics, and vocabularies. In the particular constellation of languages present in this exhibition, there is a common translation for ear—Malay’s telinga, Tagalog’s tainga, and taringa in Te Reo Māori. If language shapes how meaning is heard and made legible, this exhibition asks what conversations can be had when a root tongue is shared?

The tongue to them brings together artworks from Aotearoa, Malaysia, and the Philippines that articulate experiences of colonial impact from the vantage points of Oceania and Southeast Asia. These two regions have a particular experience of establishing the collective self in the face of a hostile other and contend with the continued ramifications this has for these respective locales. The exhibition title is taken from the poem Our Mother Tongue by Filipino nationalist and writer José Rizal, whose writing and ultimately execution by the Spanish colonial government is considered to have inspired the Philippine Revolution of the late 1890s. Although not directly involved in the planning or conduct of the revolution, Rizal is considered a national hero of the Philippines and speaks to the power of a people’s language as a tool for resistance and a symbol for freedom.

Encircling the left wing of the gallery is Malaysian artist Yee I-Lann’s TIKAR/MEJA (2019–2020). In this configuration it consists of 30 woven tikar, or mats, each depicting a single table. The tikar are woven by women of the historically nomadic and sea-based Bajau Sama Dilaut people, the traditional makers and knowledge holders of this craft. For Yee, the table represents the administrative violence of colonial control. It speaks to the authority of the pen in deals done and land carved across treaties and maps under the guise of gentlemanly negotiation. The tikar themselves counter this, retaining the open community platform of the mat. TIKAR/MEJA also assert the table’s status as foreigner—meja originates from the Portuguese mesa, which remains untranslated in the Philippines from its Spanish origins. Similarly it is a transliteration in Te Reo as tēpu.

The work of Martha Atienza and Darcell Apelu in this exhibition operate in a mode of satire and subversion as resistance against hostile forces. In Anito 1 (2011–2015) and Anito 2 (2017), Atienza documents a Christianised animist festival held on Bantayan Island where she lives. In the Ati-Atihan festival, the local community respond to often contentious current events in the form of parody. They dress up and perform reenactments relating to issues of climate change, Catholic imperatives, migratory labour, and President Rodrigo Duterte’s violent war on drugs. In Apelu’s Ingress/Egress (2025), she takes the form of a Pā waharoa or gateway and inverts its sense of welcome. In this work, her waharoa is built as an obstruction rather than a passageway, a reminder that a warm welcome has contingencies.

One linguistic trait that exists across almost all Austronesian languages is the distinct forms of we, you and them. In particular, there are usually at least two differentiations for we: an inclusive (listener included) and an exclusive (listener excluded). In Te Reo the inclusive and exclusive pronouns are tātou and mātou, respectively. These languages’ ability to immediately establish which collective is being spoken to and about lends itself to the acts of subversion in Atienza and Apelu’s works. If language has an ability to establish shared cultural understanding, then tone and nuance for native speaking audiences are able to more quickly pick up who’s in on the “joke” and who’s out.

Spatial orientation systems in Austronesian languages sit on two axes: a monsoon axis and a land-sea axis. Within a pepeha, alongside establishing one’s whakapapa and iwi, the speaker will also announce their maunga and awa. Pragmatically, a listener can make a close approximation of the speaker’s geographic coordinates within Aotearoa. Buck Nin and Heidi Brickell’s practices can be situated on this land-sea axis. Brickell’s installation Either Way Ka Mate (2023–2025) consists of rimurapa forms that can be interpreted as a hammerhead shark and a deep sea squid. This references the whakatauki “Ka mate wheke, kei mate ururoa”, which translates to “Die like a shark, lest you die like a squid” and seems to prioritise the tenacity of the shark over the floundering of a squid. Yet the wheke in Te Ao Māori, and through other parts of the Pacific, is a symbol of curiosity, exploration, and discovery.

Nin’s The Polluted Land (1993) is also included in the exhibition and will remain offsite at its home at the head office of Te Wānanga o Aotearoa Te Puna Manaaki in Te Awamutu. The four panel painting portrays a group of figures walking away from a smokey cityscape and into the arms of their tupuna, which speaks directly to its site’s history—that the land Te Wānanga o Aotearoa was built on was once a dump site and now hosts one of the largest tertiary education providers in Aotearoa. Nin was instrumental in the institution’s foundation and Māori art education at large and framed his work as bringing Māori and Pākeha worldviews together. This position speaks to Nin’s navigation of Te Ao Māori in Western systems, that of formal education and the art world of the time. Brickell is also motivated to resist binaries by bringing worlds together; embracing the characteristics of the shark and the squid to hold many wisdoms at once. In these practices, their land-sea directionalities don’t prescribe territories or prioritise one mode over another but rather orients them to the world at large.

Resisting power often demands collective action. Through the various and nuanced we, the artists in this exhibition seek to define the borders of who makes up these collectives. In bringing these practices and artworks into orientation with each other, a constellation of locales is connected by shared linguistic and cultural understanding. Can the proximity of language establish neighbourhoods based on dialogue rather than shared boundaries?

Biographies

-

Darcell Apelu of Niue, Pākehā and Te Atiawa is an artist based in Tauranga Moana. Her practice investigates social and cultural ideologies within Aotearoa with reference to themes of legacy and embedded ancestry. In 2019, Apelu was the inaugural recipient of the Te Tuhi/Yorkshire Sculpture Park Residency in the UK and in 2017 the recipient of the BC Collective Lafaiki residency in Niue. Notable exhibitions include Carry Me With You (2024–Current), SCAPE, Christchurch (2023–2024), Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki; The Death of Prosperity (2020–2022), Te Tuhi and Tauranga Art Gallery Toi Tauranga; and Ocean Memories (2021) at the Kunsthalle Faust Germany.

-

Martha Atienza lives and works in Bantayan Island, Philippines. Atienza is a Dutch-Filipino video artist exploring the format’s ability to document and question issues related to the environment, community, and development. Her video is rooted in both ecological and sociological concerns as she studies the intricate interplay between local traditions, human subjectivity, and the natural world. Atienza won the Baloise Art Prize in Art Basel in 2017 for her seminal work Our Islands (2017). Recent biennales and triennials include the 17th Istanbul Biennial (2022), Istanbul; Bangkok Art Biennale: Escape Routes (2020), BACC, Bangkok Honolulu Biennial: To Make Wrong / Right / Now (2019), Oahu, Hawaii ; and the 9th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art (2018), QAGOMA, Brisbane.

-

Heidi Brickell is of Te Hika o Pāpāuma, Ngāti Kahungunu, Rongomaiwahine, Ngāi Tara, Rangitāne, Ngāti Apakura, Airihi, Kotirana, Ingarihi, Tiamana and based in Ōtaki. Brickell has a background in Kura Kaupapa Māori education and Te Reo Māori revitalisation. Her practice embraces experimental materials, processes and forms as means to dovetail and mātauranga tuku iho as a fluidly evolving continuum. Recent solo exhibitions include Wā We Can’t Afford (2025) Te Whare Toi o Heretaunga Hastings Art Gallery; A Koru is a Trajectory (2024), Enjoy Contemporary Art Space, Te Whānganui-a-Tara Wellington; and PĀKANGA FOR THE LOSTGIRL (2022),Te Wai Ngutu Kākā Gallery, Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland, The Physics Room, Ōtautahi Christchurch and The Engine Room Te Whānganui-a-Tara Wellington. Brickell was included in Aotearoa Contemporary (2024) Toi o Tāmaki Auckland Art Gallery and Springtime is Heartbreak (2023), Te Puna o Waiwhetū Christchurch Art Gallery.

-

Buck Nin (1942–1996) of Ngāti Raukawa, Ngāti Toa, and Chinese descent, was an artist, educator, and curator who was at the forefront of the Māori art movement in the 1960s. Nin contributed to the revitalisation and promotion of Māori art practice in museums, art galleries, and the education system. He exhibited extensively in solo and group shows within New Zealand and overseas from 1963 onwards, including Kohia Ko Taikaka Anake – Artists Construct New Directions (1990), National Art Gallery, Wellington, and Te Waka Toi – Contemporary Māori Art from NZ (1992), which toured throughout North America. Nin was a key figure in establishing tertiary status for Te Wānanga o Aotearoa.

-

Yee I-Lann lives and works in Kota Kinabalu. Yee is a leading contemporary artist recognised for her ongoing research into the evolving intersection of power, colonialism, and neo-colonialism in Southeast Asia. Often centering on counter-narratives or ‘histories from below,’ she has recently begun collaborative work with sea-based and land-based communities, as well as indigenous mediums in Sabah, Malaysia. Yee has exhibited widely in museums in Asia, Europe, Australia, and the United States. Notable retrospectives include Fluid World (2011), Adelaide’s Contemporary Art Centre of South Australia, and Yee I-Lann: 2005-2016 (2016) Ayala Museum in Manila, Philippines.

Events

Deep dive: Martha Atienza and Yee I-Lann in conversation

Thursday Date Night Tours

FAM Art Tour

Question time: A lecture by Billy Tang

Visit to Te Wānanga o Aotearoa in Te Awamutu

FAM Art Tour

Audio described tour

Performance lecture: Songs of Peoplehood with Balamohan Shingade

FAM Art Tour

Artist talk with Darcell Apelu and Heidi Brickell

Reading Room

Each river every word

2025 programme

Each year we set one question which our exhibitions and events orbit in the company of artists and audiences. Across the year, we explore what this question offers us and what artworks and their authors can weave together. In 2025, we ask “is language large enough?” You can think of this as one exhibition in four parts, as a score played across a calendar, or maybe even as a forest. Join us.

Lubaina Himid

Michael Parekōwhai

Ethan Braun, Lina Grumm

Darcell Apelu

Martha Atienza

Heidi Brickell

Buck Nin

Yee I-Lann

Erika Holm

Ngaroma Riley

Tarika Sabherwal